Pressuring Biden to Declare a National Climate Emergency

In a recent podcast on climate policy, writer David Roberts points to the technological leaps in fracking as the main driver of domestic oil and gas production.

Roberts said, on Why Is This Happening, in weighing how much fossil fuel industry regulation is realistic: "Oil exploration is still going full bore and the market is hot. Almost all of these restraints or regulations that [the fossil fuel industry] are complaining about are really not going to make a substantial difference in those numbers… most of them are kind of political sops to the Greens, ‘I’m doing something about this.’" (29 minutes in)

In the conversation, Roberts was also addressing the political risks of angry voters if fossil fuel companies strike back against regulations by raising energy prices. While Roberts clearly favors strong climate policy, he said:

"It’s not like [President Biden] has done a ton of stuff affirmatively to make [increasing oil and gas production] happen, it was going to happen absent him stopping it, and I don’t think he really even had the power to stop it, he’s not been able to do [it]... the political path of least resistance is, say yes to oil and gas, and say yes to clean energy, say yes to everybody, throw out carrots to everybody, this is the easy path forward. This is true not just for the U.S. but without exception, every major fossil fuel producing country is playing this same game, they’re all helping clean energy, but none of them are substantially restraining their production." (30:50 minutes in)

My objection is that Roberts is largely presenting his view of an active debate over which executive actions to take in the climate crisis, given the Senate’s filibuster rules that prevent votes on legislation.

Restraining fossil fuel extraction was indeed among the things that more than 380 environmental groups called on President-elect Biden to do when they urged him in December 2020 to declare a climate emergency that would halt fracking on public lands and end approval of new fossil fuel projects. The letter would also have Biden implement executive actions such as reinstating the ban on crude oil exports and redirecting a portion of military spending to clean-energy infrastructure. The letter’s convening partners included the Center for Biological Diversity, Food & Water Watch, Friends of the Earth, the Indigenous Environmental Network, Indivisible, and others; national organizations signing included Greenpeace USA, the Sunrise Movement, the Action Center on Race & the Economy (ACRE), and others; international organizations included Amazon Watch, Global Witness, and Patagonia; regional organizations included 350NYC and others. To be obvious, these are not the organizations with authority over Democratic leaders' decisions about the vote sequencing of major legislation.

It's not a theoretical debate—some executive authorities were used by Biden. In June 2022, President Biden invoked the Defense Production Act (DPA) to accelerate manufacturing of clean energy technology and limit future reliance on oil and gas. Environmentalists hailed the step as revolutionary.

A year later, in June 2023, a report from the advocacy group Evergreen Action, closely tied to Democrats, made a case for the Biden administration to take further steps under the DPA, such as mandating industry studies to track progress. The American Prospect called these ideas “Biden’s Unused Clean Energy Authority.”

The debate over declaring a national climate emergency—and the powers that flow from it—matters now because fossil fuel industry allies like Sen. Joe Manchin vociferously oppose them. Without a course change, the planet will be locked in to fossil gas, ostensibly a “bridge fuel,” that will hasten the arrival of what scientists have identified as catastrophic “tipping points” in the ecosystem. Under current Senate procedural rules, which Manchin and other Democrats have recently been unwilling to change by a majority ruling, bills cannot advance to a vote in the chamber if one senator objects and there are not 60 senators to vote to move it. Also, in addition to the low-cost or no-cost authorities, the American Prospect reported in 2022 how much of the DPA’s funding is subject to a de facto veto by the Department of Defense. Progressives like Rep. Cori Bush and Sen. Bernie Sanders have introduced legislation to increase DPA clean energy funding to $100 billion, but face opposition in Congress.

Roberts is expertly aware of this debate because, to his credit, he hosted two leading proponents of the use of emergency powers for climate action on his podcast in July 2022. The two guests were Jean Su, director of the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD)’s energy justice program, and Maya Golden-Krasner, deputy director of its Climate Law Institute. They discussed potential executive actions on climate, and how much presidential authority Biden could have in leveraging the DPA and funding clean energy programs through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Roberts described himself as being more of a devil’s advocate in the debate, pointing out that conservative courts have shot down Obama-era executive actions.

Before fretting over court challenges, though, climate hawks should consider: would such a bold, immediate, jobs-creating, clean-energy-scaling path as officially declaring a national climate emergency have demonstrated that a national climate mobilization is achievable? After all, recent polls show that voters are not fans of Big Oil companies and their record annual profits. Yet the vast majority of executive actions remain on the shelf.

Looking back to the 2020 letter for the incoming Democratic government, it presented a draft executive order for Biden to consider, about six short pages in length. After declaring a national climate emergency, it contains the following sections: two, “Utilizing the Clean Air Act to Reduce Greenhouse Pollution;” four, protecting wildlife, which would “place an immediate moratorium on fracking on public lands and waters;” six, “Driving the 100% Clean Energy Transition With Green Manufacturing, Federal Procurement and Distributed Generation;” and seven, “Shifting Financial Flows From Fossil Fuels to Climate Solutions,” among others.

The possibility of a national climate emergency is not new—the presidential authorities stemming from declaring a climate emergency were raised in 2019. Media coverage of the environmental groups’ letter from the earliest days of Biden’s presidency noted that at least 38 governments including the whole of the European Union, Japan, and New Zealand “have issued some kind of resolution declaring climate change a crisis.” Since Feb. 3, 2021, the Executive Action Tracker has detailed climate and environmental actions that the Biden administration could undertake but has not, including halting new drilling and mining on public lands, or reinstating a crude oil export ban. A February 2022 report by CBD again examined the roster of executive actions available for Biden.

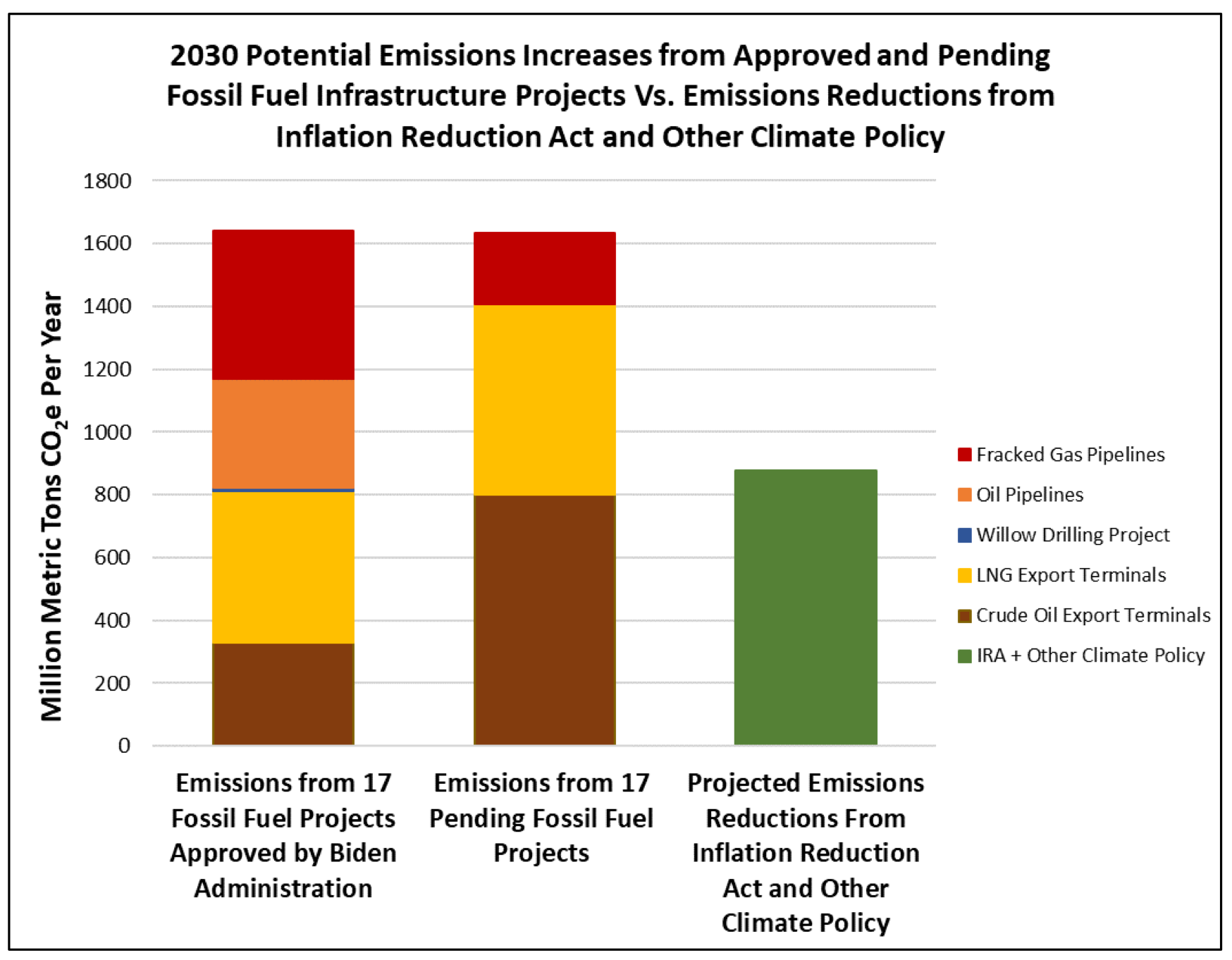

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) made historic investments in future emissions reductions—it will reduce emissions 35-43% from 2005 levels by 2030, according to the EPA last year. But the Democrats’ inability to pass the Clean Electricity Performance Program (CEPP) as part of the failed Build Back Better Act means the U.S. will likely fall short of its target of reducing emissions by half by 2030.

The costs in greenhouse gas emissions are racking up: a November 2023 analysis by CBD found, “The emissions that will result from the Biden administration’s fossil fuel project approvals are larger than the emissions reductions from the Inflation Reduction Act and other climate policies.” Executive actions to halt drilling on federal territory still have relevance: major environmental groups like Food & Water Watch (FWW), Earthjustice, Evergreen Action, and youth activists with the Sunrise Movement have made banning new fossil fuel projects on public lands a core demand of their campaigns. Even today, the Sunrise Movement’s webpage on a national climate emergency calls for the Biden administration to halt new fossil fuel development projects.

To be sure, drilling on federal lands accounts for a minority of U.S. fossil fuel production. In 2021, roughly 25% of total U.S. oil production came from federal territory, and approximately 12% of fossil gas production, according to a USAFacts post last year citing data from the Interior Department. But adopting what CBD calls a “public interest test” for fossil fuel projects is a key part of a comprehensive fossil fuel phaseout plan, which would direct the federal government to invest immediately in renewables, as laid out in a May 2023 policy brief from CBD, FWW, Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth, and other groups.

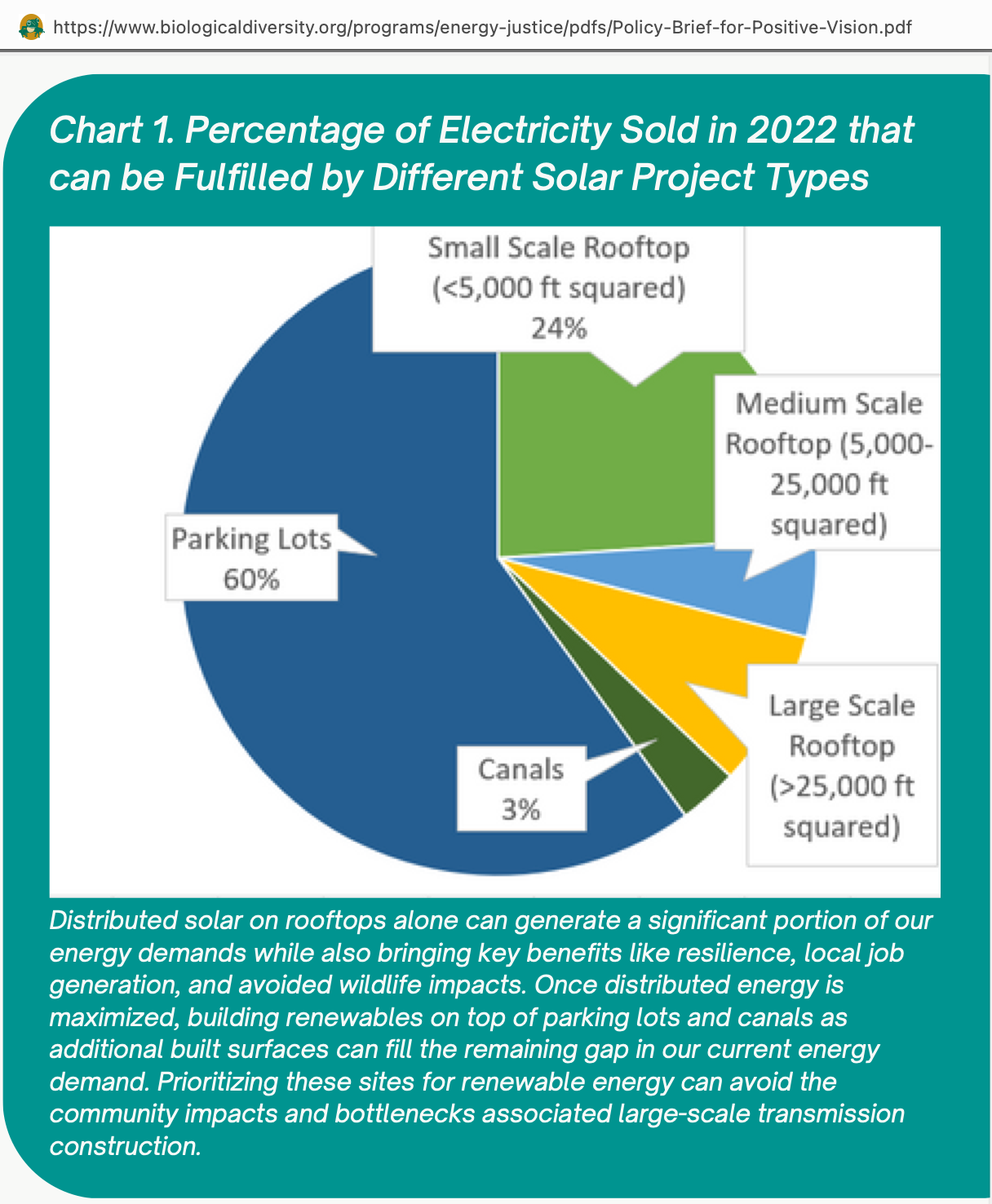

Practically, their policy brief calls for solar panels to be deployed on existing parking lots and rooftops, capturing power to be stored in batteries as part of distributed energy resources (DERs). It cites research finding (in Chart 1) that solar alone on those sites could fulfill all electricity demand circa 2022: from parking lots (60%), small rooftops (25%), medium- and large-rooftops (12%), and canals (3%). Put another way, according to a study by TIME magazine in December 2022: if half of the U.S. expanse of parking lots were covered in photovoltaic technology, some 4,822 square miles, it would generate 3,376 GW of solar capacity, which is three times all power capacity in the U.S. in 2021. More conservatively, TIME wrote, fitting 861 square miles of parking lots with solar would generate 422 GW of solar on that land alone, which would get the country halfway to its renewable energy goal for 2035 of 1,000 GW.

In addition to executive actions after declaring a national climate emergency, the policy brief calls on Congress to create a powerful planning authority and to pass bills from previous Congresses like the Low Income Solar Energy Act (H.R. 4291), the Energy Resilient Communities Act (H.R. 891), the Green New Deal for Public Schools Act of 2021 (H.R. 4442), and the Green New Deal for Public Housing Act (H.R. 2664).

Another March 2023 report by CBD examines how utility companies, powered by fossil fuels, act as obstacles to a distributed-solar energy transition. The oil industry is standing in the way of a transition to renewable energy, the Center for American Progress wrote. For years, climate journalists and policy watchdogs have exposed the delay tactics and misinformation of fossil fuel lobbying groups like the American Petroleum Institute (API).

In 2009 and the first half of 2010, the fossil fuel industry spent more than $543 million on lobbying to undermine climate action and gave out millions more in campaign contributions to members of Congress, successfully blocking the House-passed Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade climate legislation from receiving a vote in the Senate.

Democrats Won't Quit the Fossil Fuel Industry

Since Democrats lost control of the U.S. House in a 2010 Tea Party midterms wave, party leaders have not taken advantage of chances to wholeheartedly adopt investments in renewable energy as a driver of job creation.

In 2011, the Congressional Progressive Caucus released its first edition of its People’s Budget, an annual counterproposal to Democratic Party leadership on budget priorities. The progressives’ proposal would have invested $1.7 trillion in infrastructure programs, with revenues raised through a combination of winding down costly military operations abroad and reforming taxes on the wealthy and corporations. The budget would have increased discretionary spending on “renewable energy technology and deployment” by 10%, categorized as environmental programs under the Department of Energy, and launched a green jobs innovation fund. But at the time, Senate Democrats were preoccupied with deficit reduction without committing to cutting trillions of dollars in foreign war operations, and the Obama administration followed their definition of what was politically possible.

In 2015, presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders’ climate plan promoted 10 million clean energy jobs, restricting fossil fuels, and taking on the fossil fuel industry’s political power. His campaign immediately signed the No Fossil Fuel Money pledge. Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s campaign declined to sign the pledge, receiving pushback from Greenpeace, and put forward a more modest plan that foregrounded programs like challenge grants to states.

In the first half of 2019, after Democrats retook the House, party leadership under former Speaker Nancy Pelosi implemented a blacklist of vendors working with progressive challengers. Some of the party-approved firms also worked with fossil fuel industry clients like utility giant PG&E and oil major BP.

In the second half of 2019, as the Democratic National Committee (DNC) under former Chair Tom Perez rejected presidential candidates’ calls for a multi-candidate debate on the climate crisis, the party continued accepting large donations from fossil fuel industry executives. Then-candidate Biden’s climate adviser had made $1 million on the board of a liquified natural gas (LNG) company as he pursued a “middle-ground” climate policy that accepted gas.

In 2020, after Biden had won the nomination, the DNC quietly dropped language from its party platform calling for an end to fossil fuel industry subsidies. As of 2017, U.S. fossil fuel exploration and production subsidies totaled $20.5 billion annually, according to Oil Change International, a figure that could reach up to $52 billion annually, and up to $1 trillion internationally—not counting trillions more dollars every year in externalities that the planet will face. The Democratic Party’s top law firm, Perkins Coie, had lobbied against climate regulations for fossil fuel industry clients.

After winning the 2020 election, President-elect Biden tapped several fossil fuel industry allies for positions: former Rep. Cedric Richmond; as head of the National Economic Council, former BlackRock executive Brian Deese; and in the mix to lead the Department of Energy, fracking supporter and former Obama administration Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz. The Biden-Harris political team picked Jaime Harrison, a former lobbyist for BP America and “clean coal” industry coalition, to lead the DNC. As party chair, Harrison did not renominate Michelle Deatrick, chair of the Environmental Council, to be an “at-large” DNC member, among other reform-minded DNC members not picked.

The Democratic Party’s campaign arms continue to welcome campaign contributions from corporate PACs and lobbyists for the fossil fuel industry: in recent years, the DCCC’s top bundler has been Zachary Pfister, whose clients at lobbying giant Brownstein Hyatt include API. Democratic federal lawmakers continue to hold millions of dollars in personal fossil fuel company investments, as the House subsidized polluting industries and major climate legislation died in the Senate.

Former centrist Democratic lawmakers like Sen. Mary Landrieu run D.C. nonprofits—with close ties to the fossil fuel industry—that champion industry-backed plans like carbon offsets that environmental groups say are insufficient to prevent catastrophic climate degradation. Even in 2023, now under Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, House Democrats’ aligned super PAC donated to the super PAC of a “dark money” centrist nonprofit that also received $100,000 from Chevron. An ExxonMobil senior lobbyist caught in a sting video admitting to the use of “shadow groups” to prevent climate policy was an adviser to the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation. Even after the sting video, think tanks working in energy policy like the Brookings Institution and the Bipartisan Policy Center continued to accept ExxonMobil funding.

In November 2021, Biden was eager for a legislative win, as The Intercept reported, and he urged the Congressional Progressive Caucus in a phone call to break with months of strategy and vote on the corporate-backed infrastructure bill before the Build Back Better Act (BBB) and its climate measures. The BBB had been slowed in August by a group of conservative House Democrats who raised a large share of their campaign funding from corporate PACs. Biden reportedly assured House Democrats that he had a promise from fossil fuel ally Sen. Joe Manchin to allow a Senate vote on the BBB and its stronger climate measures. As a result of this decision by former Speaker Pelosi and Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, Democratic leaders gave up their leverage—and the BBB was not taken up for a vote in the Senate, as was warned by progressives and climate activists. Democrats now head into the 2024 elections without the BBB’s flagship social spending plan that would have invested hundreds of billions of dollars in programs that voters could be seeing in their daily lives, rather than the years-ahead tax credits of the IRA.

Looking ahead, there are a number of Democratic Party reforms that leaders could adopt to reduce the grip of the fossil fuel industry over energy policy: reject corporate PAC donations, reject donations from lobbyists, close the revolving door from government to lobbying—and take the No Fossil Fuel Money pledge, to reject any donations larger than $200 from any PAC, executive, or lobbyist of fossil fuel companies. But more people—more political newsreaders, podcast listeners, Democratic Party faithful, and infrequent or disaffected voters—first need to know about these options in order for party leaders to be pressured to follow them.